Cannabis products have gained popularity in recent years for their potential health benefits. From helping to alleviate chronic pain to reducing anxiety and improving sleep, there are numerous reasons why people are turning to cannabis products as a natural remedy.

One of the most well-known benefits of cannabis products is their ability to relieve pain. Whether it's from a medical condition or simply from everyday activities, many people find relief from using cannabis-based products like CBD oil or edibles. These products can help reduce inflammation and provide a sense of relaxation without the side effects often associated with traditional pain medications.

In addition to pain relief, cannabis products have also been shown to be effective in reducing anxiety and stress. By interacting with the body's endocannabinoid system, cannabinoids found in cannabis can help regulate mood and promote feelings of calmness. This makes cannabis products a popular choice for those looking for a natural way to manage their mental health.

Furthermore, cannabis products have shown promise in improving sleep quality. Many people who struggle with insomnia or other sleep disorders have found relief by incorporating CBD into their nightly routine. By promoting relaxation and reducing anxiety, cannabis products can help individuals achieve a more restful night's sleep.

Overall, the benefits of cannabis products are vast and continue to be studied by researchers around the world. As more people seek out alternative forms of medicine, it's clear that cannabis-based remedies have the potential to improve overall well-being and quality of life for many individuals.

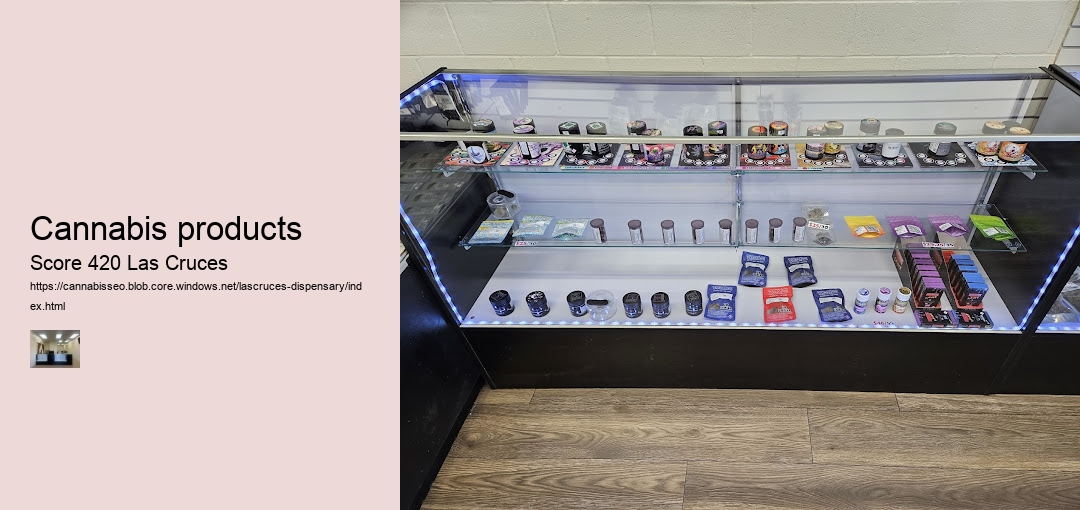

When it comes to cannabis products, there is a wide variety of options available for consumers to choose from. These products can range from traditional flower buds to concentrates, edibles, topicals, and more. Each type of product offers its own unique benefits and effects, making it important for users to explore their options and find the right fit for their needs.

One of the most popular types of cannabis products is flower, which refers to the dried buds of the cannabis plant. Flower can be smoked in joints, pipes, or bongs, providing users with a quick and potent way to experience the effects of THC and other cannabinoids. Concentrates are another common choice for cannabis consumers, offering highly potent forms of THC that can be dabbed or vaporized for intense effects.

For those looking for a more discreet or convenient option, edibles are a popular choice. These products come in various forms such as gummies, chocolates, and beverages, allowing users to enjoy the effects of cannabis without having to smoke or vape. Topicals are another type of product that can be applied directly to the skin for localized relief from pain or inflammation.

Other types of cannabis products include tinctures, capsules, and patches, each offering unique benefits and effects for users. With so many options available on the market today, it's important for consumers to do their research and choose products that align with their preferences and goals.

Overall, the diverse range of cannabis products available allows users to customize their experience based on their desired effects and consumption preferences. Whether you're looking for fast-acting relief or a long-lasting high, there is sure to be a product out there that meets your needs.

When it comes to choosing a top-rated Las Cruces dispensary, there are a few key factors that set apart the best from the rest.. One of the most important things to consider is the quality of the products available.

Posted by on 2025-03-19

Are you considering visiting a Las Cruces dispensary but not sure if it's worth your time?. Well, let me tell you, there are plenty of benefits to visiting a dispensary in this vibrant city. First and foremost, one of the main benefits of visiting a Las Cruces dispensary is the wide selection of high-quality products available.

Posted by on 2025-03-19

When you walk into a Las Cruces dispensary, you'll find a wide range of products to meet your cannabis needs.. Whether you're looking for flower, edibles, concentrates, or topicals, you'll be sure to find something that fits your preferences. One of the most popular products at dispensaries is flower, which includes strains such as indica, sativa, and hybrid.

Posted by on 2025-03-19

Choosing the right cannabis product can seem overwhelming with the countless options available in today's market. However, by considering a few key factors, you can find the perfect product to suit your needs.

First and foremost, it's important to determine what you're looking to achieve with cannabis. Are you seeking pain relief, relaxation, or a boost in creativity? Understanding your desired outcome will help narrow down the choices.

Next, consider the method of consumption that works best for you. Cannabis products come in various forms such as edibles, tinctures, topicals, and flower. Each method offers its own unique benefits and effects, so choose one that aligns with your preferences.

Additionally, take into account the potency of the product. If you're new to cannabis or have a low tolerance, start with products that have lower THC levels to avoid any unwanted side effects.

Lastly, consider any additional ingredients or terpenes present in the product. Certain terpenes can enhance specific effects of cannabis while others may offer added health benefits.

By taking these factors into consideration and experimenting with different products, you'll be able to find the right cannabis product that suits your individual needs and preferences. Remember to start low and go slow when trying out new products to ensure a positive experience.

Regulations and laws surrounding cannabis products are constantly evolving as the legalization of marijuana spreads across the globe. In many countries, cannabis products are now legal for both medical and recreational use, leading to a surge in the production and consumption of these products. However, with this growing industry comes the need for strict regulations to ensure the safety and quality of cannabis products.

Governments around the world have implemented various rules and guidelines to regulate the production, distribution, and consumption of cannabis products. These regulations often cover aspects such as packaging requirements, labeling standards, testing procedures, potency limits, and age restrictions. By enforcing these regulations, authorities aim to protect consumers from harmful or mislabeled products while also preventing illegal activities such as drug trafficking.

In addition to national regulations, there are also international treaties that govern the cultivation and trade of cannabis products. The United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs is one such treaty that aims to control the production and supply of drugs like marijuana. Countries that are party to this convention must adhere to its guidelines when it comes to regulating cannabis products within their borders.

Overall, regulations and laws surrounding cannabis products play a crucial role in shaping the industry and ensuring consumer safety. As more countries legalize marijuana, it is important for governments to stay vigilant in monitoring and enforcing these regulations to prevent potential risks associated with the use of cannabis products. By striking a balance between promoting access to safe and high-quality cannabis products while also safeguarding public health, regulators can help foster a responsible and sustainable cannabis industry for years to come.

|

Las Cruces

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Nickname:

The City of the Crosses

|

|

| Motto:

Mountains of Opportunity

|

|

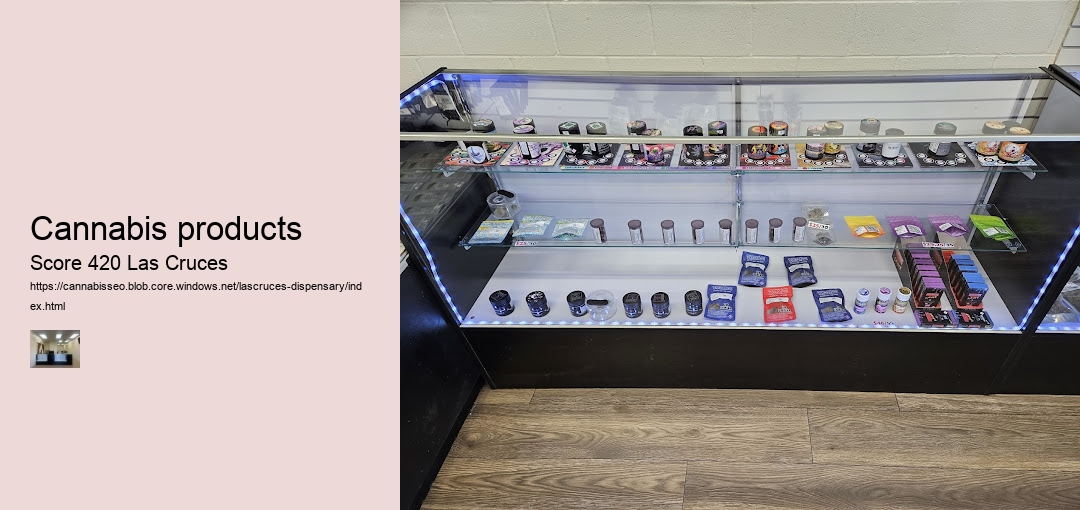

Location of Las Cruces within Doña Ana County and New Mexico

|

|

Coordinates:

32°18′52″N 106°46′44″W / 32.31444°N 106.77889°WCountry![]() United StatesState

United StatesState![]() New MexicoCountyDoña AnaFounded1849Incorporated1907[1]: 135 Government

New MexicoCountyDoña AnaFounded1849Incorporated1907[1]: 135 Government

• TypeCouncil–manager • MayorEric Enriquez • City CouncilCassie McClure, Bill Mattice, Becki Graham, Johana Bencomo, Becky Corran, Yvonne Flores • City ManagerIkani Taumoepeau • City ClerkChristine RiveraArea

77.03 sq mi (199.51 km2) • Land76.93 sq mi (199.26 km2) • Water0.10 sq mi (0.25 km2)Elevation

3,901 ft (1,189 m)Population

111,385 • Density1,447.82/sq mi (559.00/km2) • Metro

217,552 (US: 202th)DemonymLas CrucenTime zoneUTC−07:00 (Mountain) • Summer (DST)UTC−06:00 (DST)ZIP Codes

Area code575FIPS code35-39380GNIS feature ID2411629[3]Websitewww

Las Cruces (/lÉ‘ËsˈkruËsɪs/; Spanish: [las 'kruses] lit. "the crosses") is the second-most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico and the seat of Doña Ana County. As of the 2020 census, its population was 111,385,[5] making Las Cruces the most populous city in both Doña Ana County and southern New Mexico.[6] The Las Cruces metropolitan area had an estimated population of 213,849 in 2017.[7] It is the principal city of a metropolitan statistical area which encompasses all of Doña Ana County and is part of the larger El Paso–Las Cruces combined statistical area with a population of 1,088,420, making it the 56th-largest combined statistical area in the United States.

Las Cruces is the economic and geographic center of the Mesilla Valley, the agricultural region on the floodplain of the Rio Grande, which extends from Hatch to the west side of El Paso, Texas. Las Cruces is the home of New Mexico State University (NMSU), New Mexico's only land-grant university. The city's major employer is the federal government on nearby White Sands Test Facility and White Sands Missile Range. The Organ Mountains, 10 miles (16 km) to the east, are dominant in the city's landscape, along with the Doña Ana Mountains, Robledo Mountains, and Picacho Peak. Las Cruces lies 225 mi (362 km) south of Albuquerque, 42 mi (68 km) northwest of El Paso, Texas, and 41 mi (66 km) north of the Mexican border at Sunland Park.

Spaceport America, which has corporate offices in Las Cruces, operates from 55 mi (89 km) to the north; it has completed several successful crewed, suborbital flights. The city is also the headquarters for Virgin Galactic, the world's first company to offer suborbital spaceflights.[8]

During the Mexican–American War, the Battle of El Bracito was fought nearby on Christmas Day, 1846. The settlement of Las Cruces was founded in 1849, when the US Army first surveyed the town, thus opening up the area for American settlement. The town was first surveyed as the result of the American acquisition of the land surrounding Las Cruces, which later became the New Mexico Territory. This land had been ceded to the United States as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, which ended the Mexican-American War.[1]: 36, 40  The town was named "Las Cruces" after three crosses which were once located just north of the town.[9]

Initially, Mesilla became the leading settlement of the area, with more than 2,000 residents in 1860, more than twice what Las Cruces had; at that time, Mesilla had a population primarily of Mexican descent.[1]: 48  When the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway reached the area, the landowners of Mesilla refused to sell it the rights-of-way, and instead residents of Las Cruces donated the rights-of-way and land for a depot in Las Cruces.[1]: 58  The first train reached Las Cruces in 1881.[1]: 62  Las Cruces was not affected as strongly by the train as some other villages, as it was not a terminus or a crossroads, but the population did grow to 2,300 in the 1880s. Las Cruces was incorporated as a town in 1907.[1]: 135 [1]: 63

Pat Garrett is best known for his involvement in the Lincoln County War, but he also worked in Las Cruces on a famous case, the disappearance of Albert Jennings Fountain in 1896.[1]: 68

New Mexico State University was founded in 1888, and it has grown as Las Cruces has grown. The growth of Las Cruces has been attributed to the university, government jobs, and recent retirees.

The establishment of White Sands Missile Range in 1944 and White Sands Test Facility in 1963 has been integral to population growth. Las Cruces is the nearest city to each, and they provide Las Cruces' workforce with many high-paying, stable, government jobs. In recent years, the influx of retirees from out of state has also increased Las Cruces' population.

In the 1960s, Las Cruces undertook a large urban renewal project, intended to convert the old downtown into a modern city center.[1]: 115  As part of this, St. Genevieve's Catholic Church, built in 1859, was razed to make way for a downtown pedestrian mall.[1]: 44, 75, 115  The original covered walkways have been removed in favor of a more traditional main-street thoroughfare.

On February 10, 1990, seven people were shot, four fatally, in the Las Cruces bowling alley massacre. The incident remains unsolved.

The approximate elevation of Las Cruces is 3,908 feet (1,191 m) above mean sea level.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 76.6 square miles (198.5 km2), of which 0.2 square miles (0.4 km2), or 0.18%, is covered by water.[10]

Las Cruces is the center of the Organ Caldera; the Doña Ana Mountains to the north and the Organ Mountains to the east are its margins.[11] Its major eruption was 32 Ma.[12]

Doña Ana County lies within the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion, and the vegetation surrounding the built portions of the city are typical of this setting; it includes creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), soaptree (Yucca elata), tarbush (Flourensia cernua), broom dalea (Psorothamnus scoparius), and various desert grasses such as tobosa (Hilaria mutica or Pleuraphis mutica) and black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda).

The Rio Grande bisects the Mesilla Valley and passes west of Las Cruces proper, supplying irrigation water for the intensive agriculture surrounding the city.[13] Since the institution of water rights, though, the Rio Grande fills its banks only when water is released from upstream dams, which before 2020 usually occurred at least from March to September.[14] Drought conditions,[15] exacerbated by climate change, mean that the Rio Grande experiences increasingly short or small flows.[14]

Prior to farming and ranching, desert shrub vegetation extended into the valley from the adjacent deserts, including extensive stands of tornillo (Prosopis pubescens) and catclaw acacia (Acacia greggii). Desert grasslands extend in large part between the edges of Las Cruces and the lower slopes of the nearby Organ and Robledo Mountains, where grasses and assorted shrubs and cacti dominate large areas of this mostly rangeland, as well as the occasional large-lot subdivision housing.

The desert and desert grassland uplands surrounding both sides of the Mesilla Valley are often dissected with arroyos, dry streams that often carry water following heavy thunderstorms. These arroyos often contain scattered small trees, and they serve as wildlife corridors between Las Cruces' urban areas and adjacent deserts or mountains.

Unlike many cities its size, Las Cruces lacks a true central business district, because in the 1960s, an urban-renewal project tore down a large part of the original downtown. Many chain stores and national restaurants are located in the rapidly developing east side. Las Cruces' shopping mall and a variety of retail stores and restaurants are located in this area.

The historic downtown of the city is the area around Main Street, a six-block stretch of which was closed off in 1973 to form a pedestrianized shopping area. The downtown mall has an extensive farmers' market each Wednesday and Saturday mornings, where a variety of foods and cultural items can be purchased from numerous small stands that are set up by local farmers, artists, and craftspeople.[16] This area also contains museums, businesses, restaurants, churches, art galleries, and theaters, which add a great deal to the changing character of Las Cruces' historic downtown.

In August 2005, a master plan was adopted, the centerpiece of which was the restoration of narrow lanes of two-way traffic on this model portion of Main Street, which was reopened to vehicular traffic in 2012.

In February 2013, Las Cruces Mayor Ken Miyagishima announced during his "State of the City" address that a 700-acre (280 ha) park in the area behind the Las Cruces Dam was under construction, in cooperation with the Army Corps of Engineers. The area features trails through restored wetlands, and serves as a major refuge for migratory birds and a key recreational area for the city.[17]

Las Cruces has a cool desert climate (Köppen BWk). Winters alternate between colder and windier weather following trough and frontal passages, and warmer, sunnier periods; light freezes occur 69 nights on average. Spring months can be windy, particularly in the afternoons, sometimes causing periods of blowing dust and short-lived dust storms. Summers begin with the hottest weather of the year, with some extended periods of over 100 °F (37.8 °C) temperatures not uncommon, while the latter half of the summer has increased humidity and frequent afternoon thunderstorms, with slightly lower daytime temperatures. Autumns feature decreasing temperatures and precipitation.

Precipitation is very light from October to June, with only occasional winter storm systems bringing any precipitation to the Las Cruces area. Most winter moisture is in the form of rain, though some light snowfalls happen most winters, usually enough to accumulate and stay on the ground for a few hours. Summer precipitation is often from heavy thunderstorms, especially from the late summer monsoon weather pattern.

Since records began in 1892, the lowest temperature recorded at New Mexico State University has been −10 °F (−23.3 °C) on January 11, 1962 – though only 10 nights have ever fallen to or below 0 °F (−17.8 °C) – and the highest 110 °F (43.3 °C) on June 28, 1994. The lowest maximum on record is 16 °F (−8.9 °C) on January 28, 1948, and the highest minimum 83 °F (28.3 °C) on June 8, 2024. The wettest calendar year has been 1941 with 19.60 inches (497.8 mm), although 1905 with 17.09 in (434.1 mm) is the only other year to exceed 15 in (380 mm). The only months to exceed 6 in (150 mm) have been September 1941 with 7.53 in (191.3 mm) and August 1935 with 7.41 in (188.2 mm). The wettest single day has been August 30, 1935, with 6.49 in (164.8 mm) and the driest calendar year 1970 with 3.44 in (87.4 mm).

| Climate data for Las Cruces, New Mexico, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

86 (30) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

103 (39) |

95 (35) |

87 (31) |

78 (26) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 70.2 (21.2) |

76.1 (24.5) |

83.7 (28.7) |

89.1 (31.7) |

97.1 (36.2) |

103.8 (39.9) |

103.5 (39.7) |

100.1 (37.8) |

96.9 (36.1) |

90.7 (32.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

71.1 (21.7) |

105.0 (40.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.9 (14.9) |

64.1 (17.8) |

71.3 (21.8) |

78.5 (25.8) |

87.1 (30.6) |

96.2 (35.7) |

95.6 (35.3) |

93.6 (34.2) |

88.4 (31.3) |

79.6 (26.4) |

67.9 (19.9) |

58.1 (14.5) |

78.3 (25.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.2 (6.8) |

48.8 (9.3) |

55.2 (12.9) |

62.1 (16.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

80.0 (26.7) |

82.4 (28.0) |

80.6 (27.0) |

74.8 (23.8) |

64.0 (17.8) |

52.2 (11.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

63.2 (17.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

33.5 (0.8) |

39.2 (4.0) |

45.7 (7.6) |

54.2 (12.3) |

63.7 (17.6) |

69.1 (20.6) |

67.7 (19.8) |

61.1 (16.2) |

48.3 (9.1) |

36.6 (2.6) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

48.2 (9.0) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 20.8 (−6.2) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

35.9 (2.2) |

43.7 (6.5) |

55.5 (13.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

62.7 (17.1) |

51.8 (11.0) |

36.3 (2.4) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

19.9 (−6.7) |

17.7 (−7.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −10 (−23) |

−5 (−21) |

8 (−13) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

44 (7) |

30 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

−4 (−20) |

−1 (−18) |

−10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.48 (12) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.26 (6.6) |

0.22 (5.6) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.65 (17) |

1.77 (45) |

1.73 (44) |

1.41 (36) |

0.82 (21) |

0.42 (11) |

0.64 (16) |

9.14 (233) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.4 (1.0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 47.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[18] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[19] | |||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 3,836 | — | |

| 1920 | 3,989 | 4.0% | |

| 1930 | 5,811 | 45.7% | |

| 1940 | 8,385 | 44.3% | |

| 1950 | 12,325 | 47.0% | |

| 1960 | 29,387 | 138.4% | |

| 1970 | 37,857 | 28.8% | |

| 1980 | 43,377 | 14.6% | |

| 1990 | 57,866 | 33.4% | |

| 2000 | 74,267 | 28.3% | |

| 2010 | 97,618 | 31.4% | |

| 2020 | 111,385 | 14.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 2018 Estimate[20][4] |

|||

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[21] | Pop 2010[22] | Pop 2020[23] | %2000 | %2010 | %2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 31,208 | 36,577 | 35,672 | 42.02% | 37.47% | 32.03% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,486 | 1,915 | 2,392 | 2.00% | 1.96% | 2.15% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 697 | 861 | 983 | 0.94% | 0.88% | 0.88% |

| Asian (NH) | 816 | 1,421 | 1,957 | 1.10% | 1.46% | 1.76% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 34 | 77 | 76 | 0.05% | 0.08% | 0.07% |

| Some other race (NH) | 497 | 136 | 472 | 0.67% | 0.14% | 0.42% |

| Mixed or multiracial (NH) | 1,108 | 1,188 | 2,629 | 1.49% | 1.22% | 2.36% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 38,421 | 55,443 | 67,204 | 51.73% | 56.80% | 60.33% |

| Total | 74,267 | 97,618 | 111,385 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 census, Las Cruces had a population of 111,385.

Estimates for 2019 indicate that Las Cruces had a population of 103,432. Its demographics were 32.5% non-Hispanic White, 2.8% African American or Black, 1.4% Native American, 1.8% Asian, and 2.9% from two or more races: 60.5% were Hispanics or Latinos of any race. The 39,925 households had an average household size of 2.51 people each. Median household income was $43,022, and the level of people in poverty was 23.6%.[5]

As of the 2010, census Las Cruces had a population of 97,618.[10] The ethnic and racial makeup of the population was:[24]

As of the census of 2000, 74,267 people, 29,184 households, and 18,123 families were residing in the city. The population density was 1,425.7 inhabitants per square mile (550.5/km2). The 31,682 housing units had an average density of 608.2 per square mile (234.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 69.0% White, 2.3% African American, 1.7% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 21.6% from other races, and 4.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 51.7% of the population.

Of the 29,184 households, 30.4% had children under 18 living with them, 42.3% were married couples living together, 15.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.9% were not families. About 27.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.9% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.05.

In the city, the age distribution was 25.1% under 18, 16.0% from 18 to 24, 26.9% from 25 to 44, 19.0% from 45 to 64, and 13.1% who were 65 or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.3 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 91.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,375, and for a family was $37,670. Males had a median income of $30,923 versus $21,759 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,704. About 17.2% of families and 23.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.7% of those under age 18 and 9.7% of those age 65 or over.

Major employers in Las Cruces include New Mexico State University, Las Cruces Public Schools, the City of Las Cruces, Memorial Medical Center, Walmart, MountainView Regional Medical Center, Doña Ana County, Doña Ana Community College, Addus HealthCare, and NASA.

Movies and TV series shot in Las Cruces include:

Most of Las Cruces's cultural events are held late in the calendar year.[28][29]

| Festival name | Location | Description | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cowboy Days | Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum | Children's activities, cowboy food and music, mounted shooting, horseback and stagecoach rides, living history, gunfight re-enactments, and more[30] | Early March |

| Las Cruces Game Convention / CrucesCon | Las Cruces Convention Center | An annual event, gamers compete in high-level tournaments and play free games. The LCGC is a nonprofit event with 100% of the proceeds going towards the community, equipment, and future events.[31] | March |

| Cinco de Mayo Celebration | Mesilla | Celebration of Mexican heritage and pride with arts, crafts, food vendors, and Mexican music[32] | May 3–4 |

| Southern New Mexico Wine Festival | Fairgrounds | Exclusively features New Mexico wines, local foods, live music, and the University of Wine for food and wine pairings[33] | Memorial Day weekend |

| 4th of July Electric Light Parade, Celebration and Fireworks | Field of Dreams Football Stadium | Parade and fireworks display celebrating Independence Day[34] | July 3 and 4 |

| Harvest Wine Festival | Fairgrounds | Features wines from New Mexico wineries, a grape-stomping contest, several concerts throughout the weekend, food from several local vendors, and related shopping[35] | Labor Day weekend |

| Southern New Mexico State Fair | Fairgrounds | Promoting traditional agriculture, the fair boasts one of the largest junior livestock shows in the state; the fair also invites youth from six counties in New Mexico and West Texas to participate.[36] | First week of October |

| Pumpkin Harvest Festival | Lyles Farms | Features live music and the Tour de Maze (an adults only tricycle race), as well as Pumpkin Pie and a Goblin Egg Gourd Hunt [37] | Month of October |

| Day of the Walking Dead | Mesilla Valley Mall | Zombies walk around the mall.[38] | Halloween |

| Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) | Plaza in Mesilla, and Branigan Cultural Center | Originating in Mexico, this celebration of the lives of those now dead hasa focus on Mexican heritage. It is put on by the Calavera Coalition, a nonprofit organization.[39] | November 1–2 |

| Renaissance ArtsFaire | Young Park | Founded in 1971, it includes a juried art show and is put on by the Doña Ana Arts Council.[40][41][42] | November |

| Lighting of the Mesilla Plaza | Historic plaza of Mesilla | Every Christmas Eve, the historic plaza of Mesilla is lined with thousands of luminarias, which are brown bags containing candles and weighted with sand. The evening consistently attracts locals and tourists.[43] | Christmas Eve |

| Las Cruces Chile Drop | Plaza de Las Cruces | Since 2014, a vibrant 19-foot New Mexico chile, adorned with 400 feet of LED lighting, has marked the arrival of the new year, as it descends from a crane in the plaza in downtown Las Cruces. This unique celebration has become an annual tradition, accompanied by live music, a piñata, and carnival games. In 2021, the event introduced an interactive element, allowing attendees to vote on the chile's color through a QR code scan.[8] The event achieved national recognition in 2023, ranking third on USA Today's list of Best New Year's Eve Drops.[9] Additionally, in the same year, it garnered significant attention with a live broadcast on CNN, attracted over 5,000 participants, and received a visit from Congressman Gabe Vasquez and Mayor Eric Enriquez.[16] | New Year's Eve |

| Festival name | Location | Description | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Border Book Festival | Mesilla | Once it featured a trade show, readings, film festival, workshops led by local artists and writers, and discussion panels, but ended its 20-year run in April 2015.[44] The festival was founded in 1994 by authors Denise Chávez and Susan Tweit; Chávez was the executive director of the festival.[45] | April |

| The Whole Enchilada Fiesta | 1501 E. Hadley Ave. | It attracted roughly 50,000 attendees each year. The centerpiece was the making of a large, flat enchilada. The fiesta started in 1980 with a 6-foot-diameter (1.8 m) enchilada, and it grew over the years. In 2000, the fiesta's 10+1⁄2-foot-diameter (3.2 m) enchilada was certified by Guinness World Records as the world's largest. After the enchilada was assembled, it was cut into many pieces and distributed free of charge to the fiesta attendees. The enchilada was the brainchild of local restaurant owner Roberto V. Estrada, who directed its preparation each year. The celebration also featured a parade, the Whole Enchilada Fiesta Queen competition, a huachas[46] tournament, activities for kids, live music, an enchilada eating contest, a 5 kilometer road race, a one-mile race, and a car and motorcycle show.[47][48][49] After 34 years, The Whole Enchilada Fiesta's final event occurred in 2014 after Estrada had retired.[50] | Last week in September |

The New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum is state-operated and shows the history of farming and ranching in New Mexico. It is located just east of New Mexico State University.[51]

The New Mexico State University Arthropod Museum and Collection contains roughly 500,000 arthropod specimens.[52] The University Museum (Kent Hall) at New Mexico State University focuses on archeological and ethnographic collections and also has some history and natural-science collections.[53]

The Zuhl Museum (located in the Alumni and Visitors' Center) at New Mexico State University focuses on geologic collections, including the finest collection of petrified wood on display and a large fossil and mineral collection.[54]

The four city-owned museums include the Branigan Cultural Center, which examines local history through photographs, sculpture, paintings, and poetry. The building is on the National Register of Historic Places. The Las Cruces Museum of Art offers art exhibits and classes. The Las Cruces Museum of Natural History makes science and natural history more accessible to the general public and has an emphasis on local animals and plants. The Las Cruces Railroad Museum is in the historic Santa Fe Railroad station. It exhibits the impact of the railroads on the local area.[55]

The Las Cruces Symphony Orchestra is an 80-member orchestra, conducted by Dr. Ming Luke.[56] The orchestra consists of 47% students, 17% NMSU faculty, 20% other local musicians, and 16% professionals from outside Las Cruces.[57] The venue of the orchestra is the NMSU Music Center Recital Hall.[57] The orchestra received attention with the world premiere of Bill McGlaughlin's Remembering Icarus, a tribute to local radio pioneer Ralph Willis Goddard, performed by the LCSO on October 1, 2005.[58] The performance was taped and broadcast nationally on NPR's Performance Today on December 9, 2005[59] and on July 4, 2007, on Performance Today and on Sirius Satellite Radio.[60]

Several water tanks in Las Cruces have been painted with murals by Tony Pennock, including one at the intersection of Triviz Drive and Griggs Avenue.[61][62] Multimedia artist group Keep Adding has a large mural titled Wave Nest on Picacho Avenue at the Lion's Park.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Heart of Mary is the mother church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Las Cruces.

Las Cruces is the home of Vado Speedway Park, a 3/8th-mile dirt track that host the annual Wild West Shootout.

At the university level, the New Mexico State Aggies compete in Conference USA for various sports, such as men's and women's basketball, as well as football. Aggies men's basketball has had a rich history of success. Between 2010 and 2019, the Aggies made the NCAA tournament eight times. The team also reached the Final Four of the tournament in 1970. The 2014-15 NMSU women's basketball team reached the NCAA tournament for the first time since 1988, when it won both the WAC regular season and tournament championships.

The Las Cruces Kings have been a long running semiprofessional football team in the city.

Beginning in the 2010 season, the Las Cruces Vaqueros[63] were the first professional sports team in Las Cruces. In the 2011 season, the Vaqueros joined the Pecos League of Professional Baseball Clubs[64] against the White Sands Pupfish, Roswell Invaders, Ruidoso Osos, Alpine Cowboys and Carlsbad Bats.[65] The Vaqueros played in the Pecos League of Professional Baseball Clubs for the 2011–2013 seasons. The team returned for the 2015 season, but structural damage to their home ballpark in January 2016 forced them to sit out the 2016 season. They planned to return for the 2017 season.[66]

Las Cruces operates 87 city parks, 18 tennis courts, and four golf courses.[67]: 41  A list of parks, with facilities and maps, is available.[67]: 8  [68]

Las Cruces holds a Ciclovía, a citywide event featuring exercise and physical activities, on the last Sunday of each month at Meerscheidt Recreation Center.[69]

The New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum is a 47-acre (190,000 m2) interactive museum that chronicles the New Mexico's 3,000-year history of farming and ranching. The museum is part of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs.

Las Cruces is a charter city[70] (also called a home rule city) and has a council–manager form of government.[71] The city council consists of six councilors and the mayor, who chairs the meetings.[70]: Article II  The mayor is elected at-large, and each of the city councilors represents one neighborhood district within the city.[70]: Article II  Each resident of Las Cruces is thus represented by the mayor and by one city councilor. The mayor and city council members serve staggered four-year terms. As of the 2024, the mayor is Eric Enriquez. Councilors are Cassie McClure, Dist. 1; Bill Mattiace, Dist. 2; Becki Graham, Dist. 3; Johana Bencomo, Dist. 4; Becky Corran, Dist. 5; Yvonne Flores, Dist. 6.[72] Live and archived video of city council meetings are available anytime at Las Cruces, NM.[73] In the November 2019 municipal election, ranked-choice voting was used for the first time.

Public schools are in the Las Cruces Public School District, which covers the city of Las Cruces, as well as White Sands Missile Range, the settlement of Doña Ana, and the town of Mesilla. The system has 26 elementary schools, nine middle schools, and six high schools. Of the high schools, Rio Grande Preparatory is an alternative high school.[74]

Four charter schools are within the Las Cruces Public Schools. Alma d'arte is a high school with a focus on an integrated arts curriculum. Las Montañas is a charter high school that opened in fall 2007 and caters to at-risk students. New America High School offers schooling for young and older adults who want to go back to school for their diploma or GED. Academia Dolores Huerta Middle School is the only recognized dual language program in the state.[75][76]

New Mexico School for the Deaf operates a preschool facility in Las Cruces.[77]

Five private Christian schools operate in Las Cruces.[84] College Heights Kindergarten is a private Christian kindergarten, founded in 1954.[85] Desert Springs Christian Academy,[86] Las Cruces Catholic Schools,[87] Mesilla Valley Christian School, and a small independent Baptist school called Cornerstone Christian Academy[88] are other Christian schools in the area.

A secular nonprofit private school, Las Cruces Academy offers kindergarten through grade eight, with plans to eventually enroll up to grade 12.[84][89][90]

New Mexico State University (NMSU) is a land-grant university that has its main campus in Las Cruces.[91] The school was founded in 1888 as Las Cruces College, an agricultural college, and in 1889, the school became New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. It received its present name, New Mexico State University, in 1960. The NMSU Las Cruces campus had about 18,500 students enrolled as of fall 2012, and had a faculty-to-student ratio of about one to 19. NMSU offers a wide range of programs, and awards associate, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees through its main campus and four community colleges. For 10 consecutive years, NMSU has been rated as one of America's 100 Best College Buys for offering "the very highest quality education at the lowest cost" by Institutional Research & Evaluation Inc., an independent research and consulting organization for higher education. NMSU is one of only two land-grant institutions classified as Hispanic-serving by the federal government. The university is home to New Mexico's NASA Space Grant Program and is one of 52 institutions in the United States to be designated a Space Grant College. During its most recent review by NASA, NMSU was one of only 12 space grant programs in the country to receive an excellent rating.

The Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine (BCOM), a private osteopathic medical school, opened on the campus of NMSU in 2013. The first class began instruction in August 2016.

Doña Ana Community College is a branch of New Mexico State University. When it first opened in 1973, it had 500 students in six programs.[92] In the 2015–2016 school year, there were 4,997 full-time equivalent credit enrollments and 4,246 non-credit students, served by 136 full-time faculty, 401 part-time instructors, together with 225 full-time staff and 55 part-time staff.[93]

DACC operates centers in Anthony, Sunland Park, Chaparral, and White Sands Missile Range.[94] In Las Cruces, its central campus is at 3400 S. Espina Street, and its East Mesa campus is at 2800 Sonoma Ranch Boulevard. Community Education is available at all centers and campuses and also in Las Cruces at the Mesquite Neighborhood Learning Center at 804 N. Tornillo, and Workforce Center at 2345 E. Nevada Street.[95]

Thomas Branigan Memorial Library is the city's public library. It was constructed in 1979[96]: 93  and has a collection of about 185,000 items.[97] The previous library building, also called Thomas Branigan Memorial Library, opened in 1935.[96]: 68–69  That building is now the Branigan Cultural Center.[96]: 8  and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The two university libraries at the New Mexico State University campus, Branson Library and Zuhl Library, are open to the public. Any New Mexico resident can check out items from these libraries.[98]

Las Cruces is part of the El Paso – Las Cruces Designated Market Area (DMA) as defined by Nielsen Media Research. The City of Las Cruces operates CLC-TV cable channel 20, an Emmy award-winning 24-hour government-access television (GATV) and educational-access television channel on Comcast cable TV in Las Cruces. CLC-TV televises live and recorded Las Cruces city council meetings, Doña Ana County commission meetings, and Las Cruces School board meetings. The channel had previously televised City Beat, a monthly news magazine, hosted by Jennifer Martinez, with information directly related to the City of Las Cruces. The program is no longer available, but segments can still be found on Youtube.com/Clctv20. Also available for viewing are health news and other government/education related programming, as well as current weather reports and road and traffic information. CLC-TV is not a public-access television cable TV channel. In addition to a 2009 Emmy Award by the Rocky Mountain Southwest Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, CLC-TV received a first- and third-place award by the National Association of Telecommunications Officers and Advisors and five national Telly Awards, four platinum and one gold.

Las Cruces Sun-News is a daily newspaper published in Las Cruces by Digital First Media. Las Cruces Bulletin is a weekly community newspaper published in Las Cruces by FIG Publications, LLC. It is tabloid size and covers local news, business, arts, sports, and homes. The Round Up is the student newspaper at NMSU. It is tabloid size and published twice weekly. The Ink is a monthly tabloid published in Las Cruces, covering the arts and community events in southern New Mexico and West Texas.

Las Cruces has one television station, the PBS outlet KRWG-TV, operated by NMSU. The Telemundo outlet KTDO is licensed in Las Cruces, but serves El Paso. The city also receives several Albuquerque, El Paso, and Ciudad Juárez stations. Las Cruces is in Nielsen Media Research's El Paso/Las Cruces television media market.

Las Cruces has one local commercial independent cable television station called "The Las Cruces Channel" (LCC98). It can be seen on Comcast cable channel 98. LCC-98 is not a public-access television channel. The channel airs programs that are produced locally in their studio facility and by outside producers.

About 10 commercial radio stations broadcast in the Las Cruces area, running a variety of formats. Four of these stations are owned by Adams Radio Group and four are owned by Bravo Mic Communications, LLC, a Las Cruces company. The local NPR outlet is KRWG-FM, operated by NMSU, which also operates a college radio station, KRUX. KRUC is a Spanish-language station in Las Cruces. Many El Paso stations are received in Las Cruces. See list of radio stations in New Mexico for a complete list of stations. Las Cruces is in Arbitron's Las Cruces media market.

Las Cruces is served by the BNSF Railway' El Paso Subdivision, which provides freight service and extends from Belen, New Mexico to El Paso, Texas. Passenger service on this line was discontinued in 1968, due to low ridership numbers on the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway's (predecessor to the BNSF) El Pasoan train.

The city operates a small transit authority known as RoadRUNNER Transit. It operates a total of eight routes, and two Aggie routes running Mondays through Saturdays.[99]

NMDOT Park and Ride's Gold Route connects Las Cruces to El Paso on Monday through Friday during commute hours. The Silver Route connects Las Cruces to White Sands Missile Range.

South Central Regional Transit District's Green Line connects Las Cruces to Hatch, and the Red Line connects Las Cruces to Anthony.[100]

Ztrans connects Las Cruces with Alamogordo.[101]

Greyhound buses departing Las Cruces serve El Paso, Amarillo, Denver, Albuquerque, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, and San Diego.[102]

The City of Las Cruces provides water, sewer, natural gas, and solid-waste services, including recycling centers.[103] El Paso Electric is the electricity provider, CenturyLink is the telephone land line provider, and Comcast is the cable TV provider.

Memorial Medical Center is a for-profit general hospital operated by LifePoint Hospitals Inc. The physical plant is owned by the City of Las Cruces and the County of Doña Ana, which signed a 40-year, $150 million lease in 2004 with Province HealthCare, since absorbed into LifePoint.[104][105] Prior to 2004, it was leased to and operated by the nonprofit Memorial Medical Center Inc.[106][107] The hospital is a licensed, 286-bed, acute care facility and is accredited by JCAHO. It offers a wide range of patient services.[108] The University of New Mexico Cancer Center-South opened in 2006 on the MMC campus. It is 5,300 square feet (490 m2) and has 9 examination rooms.[109] The original facility was called Memorial General Hospital and was opened in April 1950 at South Alameda Boulevard and Lohman Avenue after the city obtained a $250,000 federal grant. In 1971, the city and county joined to build a new hospital on South Telshor Boulevard. In 1990, it was renamed Memorial Medical Center.[110]

MountainView Regional Medical Center is a for-profit general hospital operated by Community Health Systems (formerly Triad Hospitals). It opened for business in August 2002. It is a 168-bed facility with a wide range of patient services.[111]

Mesilla Valley Hospital is a 125-bed, private, psychiatric hospital operated by Universal Health Services. It is an acute inpatient and residential facility offering a variety of treatments for behavioral health issues.[112]

Rehabilitation Hospital of Southern New Mexico is a 40-bed, rehabilitative-care hospital, operated by Ernest Health Inc. It opened January 2005. It treats patients after they have been cared for at general hospitals for injuries or strokes.[113][114]

Advanced Care Hospital of Southern New Mexico is a 20-bed, long-term, acute care facility operated by Ernest Health Inc. It opened in July 2007.[115]

Las Cruces has two sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Las Cruces Sister Cities Foundation[119] is responsible for overseeing sister cities activities on behalf of the citizens of Las Cruces. The Foundation was created in 1989 to officially recognize a relationship that began in 1982 with exchanges between Doña Ana Community College and the Centro de Bachilleratio Technológico Industrial y de Servicios Numero 4 of Lerdo, Durango, Mexico. In 1993, a second partnership was established with Nienburg, Lower Saxony, Germany, which grew from a school exchange between Mayfield High School and Albert Schweitzer School.[citation needed]

The Late Eocene—Oligocene peak of Cenozoic volcanism in southwestern New Mexico

| Cannabis

Temporal range: Early Miocene – Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Common hemp | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis L. |

| Species[1] | |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

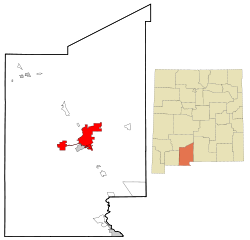

Cannabis (/ˈkænÉ™bɪs/ ⓘ)[2] is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia.[3][4][5] However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species being recognized: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis. Alternatively, C. ruderalis may be included within C. sativa, or all three may be treated as subspecies of C. sativa,[1][6][7][8] or C. sativa may be accepted as a single undivided species.[9]

The plant is also known as hemp, although this term is usually used to refer only to varieties cultivated for non-drug use. Hemp has long been used for fibre, seeds and their oils, leaves for use as vegetables, and juice. Industrial hemp textile products are made from cannabis plants selected to produce an abundance of fibre.

Cannabis also has a long history of being used for medicinal purposes, and as a recreational drug known by several slang terms, such as marijuana, pot or weed. Various cannabis strains have been bred, often selectively to produce high or low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid and the plant's principal psychoactive constituent. Compounds such as hashish and hash oil are extracted from the plant.[10] More recently, there has been interest in other cannabinoids like cannabidiol (CBD), cannabigerol (CBG), and cannabinol (CBN).

Cannabis is a Scythian word.[11][12][13] The ancient Greeks learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.[12] In Akkadian, cannabis was known as qunubu (ðŽ¯ðŽ«ðŽ ðŽð‚).[12] The word was adopted in to the Hebrew language as qaneh bosem (×§Ö¸× Ö¶×” בֹּשׂ×).[12]

Cannabis is an annual, dioecious, flowering herb. The leaves are palmately compound or digitate, with serrate leaflets.[14] The first pair of leaves usually have a single leaflet, the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on variety and growing conditions. At the top of a flowering plant, this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite leaf arrangement and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant.

The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic venation pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of Cannabis leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in Cannabis this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of Cannabis also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.[15]

All known strains of Cannabis are wind-pollinated[16] and the fruit is an achene.[17] Most strains of Cannabis are short day plants,[16] with the possible exception of C. sativa subsp. sativa var. spontanea (= C. ruderalis), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be day-neutral.

Cannabis is predominantly dioecious,[16][18] having imperfect flowers, with staminate "male" and pistillate "female" flowers occurring on separate plants.[19] "At a very early period the Chinese recognized the Cannabis plant as dioecious",[20] and the (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya dictionary defined xi 枲 "male Cannabis" and fu 莩 (or ju 苴) "female Cannabis".[21] Male flowers are normally borne on loose panicles, and female flowers are borne on racemes.[22]

Many monoecious varieties have also been described,[23] in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.[24] (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in Cannabis – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.[25][26][27] Many populations have been described as sexually labile.[28][29][30]

As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, Cannabis exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.[31] Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,[25] but sativa strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of inbreeding.

Cannabis has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of sex determination among the dioecious plants.[31] Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in Cannabis.

Based on studies of sex reversal in hemp, it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an XY sex-determination system is present.[29] At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The X:A system was first described in Drosophila spp in 1925.[32] Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,[33] and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.[30]

Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.[18] Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.[34]

Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for Cannabis. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".[18]

The question of whether heteromorphic sex chromosomes are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a karyotype. Cannabis was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped; however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious "Kentucky" hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious "Kentucky" hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious "Kentucky" hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.[35] According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of Cannabis had been published as of 1996.[36] Proponents of the XY system state that Y chromosome is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.[37]

More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors[38][39] have used random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) to isolate several genetic marker sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and amplified fragment length polymorphism.[40][28][41] Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating,

It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.[18]

Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.[42] Many researchers have suggested that sex in Cannabis is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.[30] Ainsworth reviews that treatment with auxin and ethylene have feminizing effects, and that treatment with cytokinins and gibberellins have masculinizing effects.[18] It has been reported that sex can be reversed in Cannabis using chemical treatment.[43] A polymerase chain reaction-based method for the detection of female-associated DNA polymorphisms by genotyping has been developed.[44]

Cannabis plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their defense against herbivory. One group of these is called cannabinoids, which induce mental and physical effects when consumed.

Cannabinoids, terpenes, terpenoids, and other compounds are secreted by glandular trichomes that occur most abundantly on the floral calyxes and bracts of female plants.[46]

Cannabis, like many organisms, is diploid, having a chromosome complement of 2n=20, although polyploid individuals have been artificially produced.[47] The first genome sequence of Cannabis, which is estimated to be 820 Mb in size, was published in 2011 by a team of Canadian scientists.[48]

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[49] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[50][51]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[52]

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[53] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[54] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[55] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[56] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[40] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[56][57]

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[58] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[59] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[59] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[47] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[60] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[61][62][63]

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[64] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classification attempts resulted in a four group division:[65]

In 1785, evolutionary biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica Lam.[66] Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described C. indica as having poorer fiber quality than C. sativa, but greater utility as an inebriant. Also, C. indica was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were characteristics noted by the botanist.[65]

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based on a clear distinction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[65]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[67] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union, where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[68]

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[52] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[57][67] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[69] and Emboden (1974):[70] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[65]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[52][71][72] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[73]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[61][62] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[74]

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[75] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of phenotypic characters.[56][67][76]

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[77][78][79][80] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[81] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[82] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[83]

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[84][85][28][86][87] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[57] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[60] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[88]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[89]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[90] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018[update]) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[91]

The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type Cannabis. Cannabis aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology, native range, aroma, and subjective psychoactive characteristics. "Sativa" is the most widespread variety, which is usually tall, laxly branched, and found in warm lowland regions. "Indica" designates shorter, bushier plants adapted to cooler climates and highland environments. "Ruderalis" is the informal name for the short plants that grow wild in Europe and Central Asia.[83]

Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. indica var. indica, "Indica" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. i. kafiristanica (also known as afghanica), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into C. sativa subsp. sativa. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.[83] Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results.

Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type Cannabis often describe the ancestry or gross phenotypic characteristics of cultivars by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.[83]

Cannabis likely split from its closest relative, Humulus (hops), during the mid Oligocene, around 27.8 million years ago according to molecular clock estimates. The centre of origin of Cannabis is likely in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. The pollen of Humulus and Cannabis are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from Cannabis is from Ningxia, China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, dating to the early Miocene, around 19.6 million years ago. Cannabis was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known Cannabis in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.[92]

Cannabis is used for a wide variety of purposes.

According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period.[5] The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.[93] The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian Herodotus's reference to the central Eurasian Scythians taking cannabis steam baths.[94] His (c. 440 BCE) Histories records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed [presumably, flowers], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."[95] Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis.

In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the Shennong Bencaojing (3rd century AD).[96] Cannabis smoke was inhaled by Daoists, who burned it in incense burners.[96]

In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.[97][98][99][100]

Cannabinol (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.[101]

Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis were produced legally.[102]

Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.[when?][104] As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried marijuana, hashish, or various extracts collectively known as hashish oil.[10]

Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a smoking pipe, bong or vaporizer.[105] However, if a large amount is taken orally the effects may last much longer. After 24 hours to a few days, minuscule psychoactive effects may be felt, depending on dosage, frequency and tolerance to the drug.

Cannabidiol (CBD), which has no intoxicating effects by itself[55] (although sometimes showing a small stimulant effect, similar to caffeine),[106] is thought to attenuate (i.e., reduce)[107] the anxiety-inducing effects of high doses of THC, particularly if administered orally prior to THC exposure.[108]

According to Delphic analysis by British researchers in 2007, cannabis has a lower risk factor for dependence compared to both nicotine and alcohol.[109] However, everyday use of cannabis may be correlated with psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability or insomnia,[105] and susceptibility to a panic attack may increase as levels of THC metabolites rise.[110][111] Cannabis withdrawal symptoms are typically mild and are not life-threatening.[112] Risk of adverse outcomes from cannabis use may be reduced by implementation of evidence-based education and intervention tools communicated to the public with practical regulation measures.[113]

In 2014 there were an estimated 182.5 million cannabis users worldwide (3.8% of the global population aged 15–64).[114] This percentage did not change significantly between 1998 and 2014.[114]

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, in an effort to treat disease or improve symptoms. Cannabis is used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, and to treat chronic pain and muscle spasms.[115][116] Cannabinoids are under preliminary research for their potential to affect stroke.[117] Evidence is lacking for depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis.[118] Two extracts of cannabis – dronabinol and nabilone – are approved by the FDA as medications in pill form for treating the side effects of chemotherapy and AIDS.[119]

Short-term use increases both minor and major adverse effects.[116] Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, vomiting, and hallucinations.[116] Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear.[120] Concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, schizophrenia in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.[115]

The term hemp is used to name the durable soft fiber from the Cannabis plant stem (stalk). Cannabis sativa cultivars are used for fibers due to their long stems; Sativa varieties may grow more than six metres tall. However, hemp can refer to any industrial or foodstuff product that is not intended for use as a drug. Many countries regulate limits for psychoactive compound (THC) concentrations in products labeled as hemp.

Cannabis for industrial uses is valuable in tens of thousands of commercial products, especially as fibre[121] ranging from paper, cordage, construction material and textiles in general, to clothing. Hemp is stronger and longer-lasting than cotton. It also is a useful source of foodstuffs (hemp milk, hemp seed, hemp oil) and biofuels. Hemp has been used by many civilizations, from China to Europe (and later North America) during the last 12,000 years.[121][122] In modern times novel applications and improvements have been explored with modest commercial success.[123][124]

In the US, "industrial hemp" is classified by the federal government as cannabis containing no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. This classification was established in the 2018 Farm Bill and was refined to include hemp-sourced extracts, cannabinoids, and derivatives in the definition of hemp.[125]

The Cannabis plant has a history of medicinal use dating back thousands of years across many cultures.[126] The Yanghai Tombs, a vast ancient cemetery (54 000 m2) situated in the Turfan district of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China, have revealed the 2700-year-old grave of a shaman. He is thought to have belonged to the Jushi culture recorded in the area centuries later in the Hanshu, Chap 96B.[127] Near the head and foot of the shaman was a large leather basket and wooden bowl filled with 789g of cannabis, superbly preserved by climatic and burial conditions. An international team demonstrated that this material contained THC. The cannabis was presumably employed by this culture as a medicinal or psychoactive agent, or an aid to divination. This is the oldest documentation of cannabis as a pharmacologically active agent.[128] The earliest evidence of cannabis smoking has been found in the 2,500-year-old tombs of Jirzankal Cemetery in the Pamir Mountains in Western China, where cannabis residue were found in burners with charred pebbles possibly used during funeral rituals.[129][130]