Seattle, like many other cities, is home to a variety of pests that can cause havoc in our homes and businesses. Some of the most common pests found in Seattle include rodents, ants, spiders, cockroaches, and bed bugs.

Rodents such as rats and mice are notorious for sneaking into our homes in search of food and shelter. Not only do they spread diseases, but they can also cause damage to our property by gnawing on wires and insulation.

Ants are another common pest found in Seattle. They are notorious for invading our kitchens and pantries in search of crumbs and spills. While some ants may seem harmless, others like carpenter ants can cause structural damage by burrowing into wood.

Spiders are also prevalent in Seattle, with some species such as black widows and brown recluses posing a threat to humans with their venomous bites. Additionally, their webs can be unsightly and difficult to remove.

Cockroaches are yet another pest commonly found in Seattle. These resilient insects can quickly multiply if left unchecked, spreading bacteria and allergens throughout our homes.

Finally, bed bugs have become an increasing problem in Seattle in recent years. These tiny parasites feed on human blood while we sleep, leaving behind itchy red welts on our skin.

Dealing with these pests can be a daunting task, which is why professional pest control services are often necessary to effectively eliminate them from our homes and businesses. By understanding the types of pests commonly found in Seattle and taking preventative measures, we can protect ourselves from the potential dangers they pose.

Pest control is a crucial aspect of maintaining a safe and healthy environment in Seattle. With the city's diverse ecosystem, pests such as rodents, insects, and other unwanted critters can easily invade homes and businesses, causing damage and spreading diseases.

Professional pest control services in Seattle play a vital role in effectively managing pest infestations. These experts are trained to identify the root cause of the problem and implement tailored solutions to eliminate pests from your property. They use advanced techniques and environmentally friendly products to ensure that your living or working space remains pest-free without harming the ecosystem.

By hiring professional pest control services in Seattle, you can prevent potential health hazards associated with pests, protect your property from damage, and maintain peace of mind knowing that your home or business is free from unwanted intruders. Additionally, regular pest control treatments can help prevent future infestations, saving you time and money in the long run.

In conclusion, investing in professional pest control services in Seattle is essential for maintaining a clean and healthy environment. By entrusting experts to handle pest infestations, you can enjoy a pest-free space while contributing to the overall well-being of the city. Don't wait until pests become a major issue – contact professional pest control services today for effective solutions tailored to your specific needs.

Are you dealing with pesky pests invading your home or business in Seattle?. It can be incredibly frustrating to have unwanted guests like ants, rodents, or bed bugs wreaking havoc on your property.

Posted by on 2025-03-05

When it comes to dealing with pest control issues in Seattle, one of the most common questions that homeowners have is about the average response time for pest control services.. This is a valid concern, as no one wants to be left waiting around for days on end while pests continue to wreak havoc in their home. In general, the average response time for pest control services in Seattle can vary depending on a number of factors.

Posted by on 2025-03-05

Pests are a common problem for many Seattle residents, especially during different seasons of the year.. From rodents to insects, these unwanted guests can wreak havoc on homes and businesses if not dealt with properly.

Posted by on 2025-03-05

When it comes to dealing with pesky pests in Seattle, many people are looking for eco-friendly options that are safe for both their families and the environment. Luckily, there are a variety of environmentally friendly pest control solutions available in the Emerald City.

One popular option is using natural repellents such as essential oils or plant-based sprays to deter insects like ants, spiders, and roaches. These products are non-toxic and can be effective at keeping pests at bay without the use of harmful chemicals.

Another eco-friendly approach is to practice integrated pest management (IPM), which focuses on preventing infestations through methods like sealing up cracks and crevices, maintaining cleanliness, and removing sources of food and water for pests. By taking a proactive approach to pest control, you can reduce the need for chemical treatments.

For those who do require professional help with their pest problems, there are green pest control companies in Seattle that specialize in using environmentally friendly methods. These companies may utilize techniques such as heat treatment, trapping, or biological controls to eradicate pests without harming beneficial insects or plants.

Overall, choosing eco-friendly pest control options in Seattle not only helps protect your home and family from unwanted intruders but also contributes to a healthier environment for all. By embracing sustainable practices when dealing with pests, you can enjoy peace of mind knowing that you're doing your part to preserve the beauty of the Pacific Northwest.

Pest infestations can be a major headache for homeowners in Seattle, but there are steps you can take to prevent them from taking over your home. Here are some tips to help keep pests at bay.

First and foremost, make sure to keep your home clean and tidy. Pests are attracted to food crumbs and spills, so be sure to regularly sweep and vacuum floors, wipe down counters, and store food in airtight containers. Don't forget to take out the trash regularly as well.

Seal up any cracks or crevices in your home where pests could enter. This includes gaps around windows and doors, as well as holes in walls or floors. You can use caulk or weather stripping to seal these areas and prevent pests from finding their way inside.

Keep your yard neat and well-maintained. Trim back bushes and trees that are close to your home, as pests like rodents and insects can use them as a bridge to get inside. Make sure to also remove any standing water sources like birdbaths or clogged gutters, as these can attract pests looking for a drink.

Consider installing screens on windows and doors to keep pests out while still allowing fresh air in. You can also use mesh covers on vents and chimneys to prevent pests from entering through these openings.

If you do find yourself dealing with a pest infestation, it's best to contact a professional pest control service right away. They have the knowledge and tools needed to effectively remove pests from your home and prevent them from coming back.

By following these tips for preventing pest infestations in Seattle, you can help protect your home from unwanted invaders and enjoy peace of mind knowing that your space is clean and pest-free.

Pest control is the regulation or management of a species defined as a pest; such as any animal, plant or fungus that impacts adversely on human activities or environment.[1] The human response depends on the importance of the damage done and will range from tolerance, through deterrence and management, to attempts to completely eradicate the pest. Pest control measures may be performed as part of an integrated pest management strategy.

In agriculture, pests are kept at bay by mechanical, cultural, chemical and biological means.[2] Ploughing and cultivation of the soil before sowing mitigate the pest burden, and crop rotation helps to reduce the build-up of a certain pest species. Concern about environment means limiting the use of pesticides in favour of other methods. This can be achieved by monitoring the crop, only applying pesticides when necessary, and by growing varieties and crops which are resistant to pests. Where possible, biological means are used, encouraging the natural enemies of the pests and introducing suitable predators or parasites.[3]

In homes and urban environments, the pests are the rodents, birds, insects and other organisms that share the habitat with humans, and that feed on or spoil possessions. Control of these pests is attempted through exclusion or quarantine, repulsion, physical removal or chemical means.[4] Alternatively, various methods of biological control can be used including sterilisation programmes.

Pest control is at least as old as agriculture, as there has always been a need to keep crops free from pests. As long ago as 3000 BC in Egypt, cats were used to control pests of grain stores such as rodents.[5][6] Ferrets were domesticated by 1500 BC in Europe for use as mousers. Mongooses were introduced into homes to control rodents and snakes, probably by the ancient Egyptians.[7]

The conventional approach was probably the first to be employed, since it is comparatively easy to destroy weeds by burning them or ploughing them under, and to kill larger competing herbivores. Techniques such as crop rotation, companion planting (also known as intercropping or mixed cropping), and the selective breeding of pest-resistant cultivars have a long history.[8]

Chemical pesticides were first used around 2500 BC, when the Sumerians used sulphur compounds as insecticides.[9] Modern pest control was stimulated by the spread across the United States of the Colorado potato beetle. After much discussion, arsenical compounds were used to control the beetle and the predicted poisoning of the human population did not occur. This led the way to a widespread acceptance of insecticides across the continent.[10] With the industrialisation and mechanization of agriculture in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the introduction of the insecticides pyrethrum and derris, chemical pest control became widespread. In the 20th century, the discovery of several synthetic insecticides, such as DDT, and herbicides boosted this development.[10]

The harmful side effect of pesticides on humans has now resulted in the development of newer approaches, such as the use of biological control to eliminate the ability of pests to reproduce or to modify their behavior to make them less troublesome.[citation needed] Biological control is first recorded around 300 AD in China, when colonies of weaver ants, Oecophylla smaragdina, were intentionally placed in citrus plantations to control beetles and caterpillars.[9] Also around 4000 BC in China, ducks were used in paddy fields to consume pests, as illustrated in ancient cave art. In 1762, an Indian mynah was brought to Mauritius to control locusts, and about the same time, citrus trees in Burma were connected by bamboos to allow ants to pass between them and help control caterpillars. In the 1880s, ladybirds were used in citrus plantations in California to control scale insects, and other biological control experiments followed. The introduction of DDT, a cheap and effective compound, put an effective stop to biological control experiments. By the 1960s, problems of resistance to chemicals and damage to the environment began to emerge, and biological control had a renaissance. Chemical pest control is still the predominant type of pest control today, although a renewed interest in traditional and biological pest control developed towards the end of the 20th century and continues to this day.[11]

Biological pest control is a method of controlling pests such as insects and mites by using other organisms.[12] It relies on predation, parasitism, herbivory, parasitody or other natural mechanisms, but typically also involves an active human management role. Classical biological control involves the introduction of natural enemies of the pest that are bred in the laboratory and released into the environment. An alternative approach is to augment the natural enemies that occur in a particular area by releasing more, either in small, repeated batches, or in a single large-scale release. Ideally, the released organism will breed and survive, and provide long-term control.[13] Biological control can be an important component of an integrated pest management programme.

For example: mosquitoes are often controlled by putting Bt Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. israelensis, a bacterium that infects and kills mosquito larvae, in local water sources.[14]

Mechanical pest control is the use of hands-on techniques as well as simple equipment and devices, that provides a protective barrier between plants and insects. This is referred to as tillage and is one of the oldest methods of weed control as well as being useful for pest control; wireworms, the larvae of the common click beetle, are very destructive pests of newly ploughed grassland, and repeated cultivation exposes them to the birds and other predators that feed on them.[15]

Crop rotation can help to control pests by depriving them of their host plants. It is a major tactic in the control of corn rootworm, and has reduced early season incidence of Colorado potato beetle by as much as 95%.[16]

A trap crop is a crop of a plant that attracts pests, diverting them from nearby crops.[17] Pests aggregated on the trap crop can be more easily controlled using pesticides or other methods.[18] However, trap-cropping, on its own, has often failed to cost effectively reduce pest densities on large commercial scales, without the use of pesticides, possibly due to the pests' ability to disperse back into the main field.[18]

Pesticides are substances applied to crops to control pests, they include herbicides to kill weeds, fungicides to kill fungi and insecticides to kill insects. They can be applied as sprays by hand, tractors, or aircraft or as seed dressings. To be effective, the correct substance must be applied at the correct time and the method of application is important to ensure adequate coverage and retention on the crop. The killing of natural enemies of the target pest should be minimized. This is particularly important in countries where there are natural reservoirs of pests and their enemies in the countryside surrounding plantation crops, and these co-exist in a delicate balance. Often in less-developed countries, the crops are well adapted to the local situation and no pesticides are needed. Where progressive farmers are using fertilizers to grow improved crop varieties, these are often more susceptible to pest damage, but the indiscriminate application of pesticides may be detrimental in the longer term.[19][unreliable source?][failed verification] The efficacy of chemical pesticides tends to diminish over time. This is because any organism that manages to survive the initial application will pass on its genes to its offspring and a resistant strain will be developed. In this way, some of the most serious pests have developed resistance and are no longer killed by pesticides that used to kill their ancestors. This necessitates higher concentrations of chemical, more frequent applications and a movement to more expensive formulations.[20]

Pesticides are intended to kill pests, but many have detrimental effects on non-target species; of particular concern is the damage done to honey-bees, solitary bees and other pollinating insects and in this regard, the time of day when the spray is applied can be important.[21] The widely used neonicotinoids have been banned on flowering crops in some countries because of their effects on bees.[21] Some pesticides may cause cancer and other health problems in humans, as well as being harmful to wildlife.[22] There can be acute effects immediately after exposure or chronic effects after continuous low-level, or occasional exposure.[23] Maximum residue limits for pesticides in foodstuffs and animal feed are set by many nations.[24]

Using crops with inheritable resistance to pests is referred to as host-plant resistance and reduces the need for pesticide use. These crops can harm or even kill pests, repel feeding, prevent colonization, or tolerate the presence of a pest without significantly impacting yield.[25][26][27] Resistance can also occur through genetic engineering to have traits with resistance to insects, such as with Bt corn, or papaya resistance to ringspot virus.[28] When farmers are purchasing seed, variety information often includes resistance to selected pests in addition to other traits.[29]

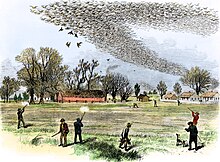

Pest control can also be achieved via culling the pest animals — generally small- to medium-sized wild or feral mammals or birds that inhabit the ecological niches near farms, pastures or other human settlements — by employing human hunters or trappers to physically track down, kill and remove them from the area. The culled animals, known as vermin, may be targeted because they are deemed harmful to agricultural crops, livestock or facilities; serve as hosts or vectors that transmit pathogens across species or to humans; or for population control as a mean of protecting other vulnerable species and ecosystems.[30]

Pest control via hunting, like all forms of harvest, has imposed an artificial selective pressure on the organisms being targeted. While varmint hunting is potentially selecting for desired behavioural and demographic changes (e.g. animals avoiding human populated areas, crops and livestock), it can also result in unpredicted outcomes such as the targeted animal adapting for faster reproductive cycles.[31]

Forest pests present a significant problem because it is not easy to access the canopy and monitor pest populations. In addition, forestry pests such as bark beetles, kept under control by natural enemies in their native range, may be transported large distances in cut timber to places where they have no natural predators, enabling them to cause extensive economic damage.[32] Pheromone traps have been used to monitor pest populations in the canopy. These release volatile chemicals that attract males. Pheromone traps can detect the arrival of pests or alert foresters to outbreaks. For example, the spruce budworm, a destructive pest of spruce and balsam fir, has been monitored using pheromone traps in Canadian forests for several decades.[33] In some regions, such as New Brunswick, areas of forest are sprayed with pesticide to control the budworm population and prevent the damage caused during outbreaks.[34]

Many unwelcome animals visit or make their home in residential buildings, industrial sites and urban areas. Some contaminate foodstuffs, damage structural timbers, chew through fabrics or infest stored dry goods. Some inflict great economic loss, others carry diseases or cause fire hazards, and some are just a nuisance. Control of these pests has been attempted by improving sanitation and garbage control, modifying the habitat, and using repellents, growth regulators, traps, baits and pesticides.[35]

Physical pest control involves trapping or killing pests such as insects and rodents. Historically, local people or paid rat-catchers caught and killed rodents using dogs and traps.[36] On a domestic scale, sticky flypapers are used to trap flies. In larger buildings, insects may be trapped using such means as pheromones, synthetic volatile chemicals or ultraviolet light to attract the insects; some have a sticky base or an electrically charged grid to kill them. Glueboards are sometimes used for monitoring cockroaches and to catch rodents. Rodents can be killed by suitably baited spring traps and can be caught in cage traps for relocation. Talcum powder or "tracking powder" can be used to establish routes used by rodents inside buildings and acoustic devices can be used for detecting beetles in structural timbers.[35]

Historically, firearms have been one of the primary methods used for pest control. "Garden Guns" are smooth bore shotguns specifically made to fire .22 caliber snake shot or 9mm Flobert, and are commonly used by gardeners and farmers for snakes, rodents, birds, and other pest. Garden Guns are short-range weapons that can do little harm past 15 to 20 yards, and they're relatively quiet when fired with snake shot, compared to standard ammunition. These guns are especially effective inside of barns and sheds, as the snake shot will not shoot holes in the roof or walls, or more importantly, injure livestock with a ricochet. They are also used for pest control at airports, warehouses, stockyards, etc.[37]

The most common shot cartridge is .22 Long Rifle loaded with #12 shot. At a distance of about 10 ft (3.0 m), which is about the maximum effective range, the pattern is about 8 in (20 cm) in diameter from a standard rifle. Special smoothbore shotguns, such as the Marlin Model 25MG can produce effective patterns out to 15 or 20 yards using .22 WMR shotshells, which hold 1/8 oz. of #12 shot contained in a plastic capsule.

Poisoned bait is a common method for controlling rats, mice, birds, slugs, snails, ants, cockroaches, and other pests. The basic granules, or other formulation, contains a food attractant for the target species and a suitable poison. For ants, a slow-acting toxin is needed so that the workers have time to carry the substance back to the colony, and for flies, a quick-acting substance to prevent further egg-laying and nuisance.[38] Baits for slugs and snails often contain the molluscide metaldehyde, dangerous to children and household pets.[39]

An article in Scientific American in 1885 described effective elimination of a cockroach infestation using fresh cucumber peels.[40]

Warfarin has traditionally been used to kill rodents, but many populations have developed resistance to this anticoagulant, and difenacoum may be substituted. These are cumulative poisons, requiring bait stations to be topped up regularly.[38] Poisoned meat has been used for centuries to kill animals such as wolves[41] and birds of prey.[42] Poisoned carcasses however kill a wide range of carrion feeders, not only the targeted species.[41] Raptors in Israel were nearly wiped out following a period of intense poisoning of rats and other crop pests.[43]

Fumigation is the treatment of a structure to kill pests such as wood-boring beetles by sealing it or surrounding it with an airtight cover such as a tent, and fogging with liquid insecticide for an extended period, typically of 24–72 hours. This is costly and inconvenient as the structure cannot be used during the treatment, but it targets all life stages of pests.[44]

An alternative, space treatment, is fogging or misting to disperse a liquid insecticide in the atmosphere within a building without evacuation or airtight sealing, allowing most work within the building to continue, at the cost of reduced penetration. Contact insecticides are generally used to minimize long-lasting residual effects.[44]

Populations of pest insects can sometimes be dramatically reduced by the release of sterile individuals. This involves the mass rearing of a pest, sterilising it by means of X-rays or some other means, and releasing it into a wild population. It is particularly useful where a female only mates once and where the insect does not disperse widely.[45] This technique has been successfully used against the New World screw-worm fly, some species of tsetse fly, tropical fruit flies, the pink bollworm and the codling moth, among others.[46]

To chemically sterilize pests using chemosterilants, laboratory studies conducted using U-5897 (3-chloro-1,2-propanediol) attempted in the early 1970s for rat control, although these proved unsuccessful.[47] In 2013, New York City tested sterilization traps,[48] demonstrating a 43% reduction in rat populations.[48] The product ContraPest was approved for the sterilization of rodents by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in August 2016 as a chemosterilant.[49]

Boron, a known pesticide can be impregnated into the paper fibers of cellulose insulation at certain levels to achieve a mechanical kill factor for self-grooming insects such as ants, cockroaches, termites, and more. The addition of insulation into the attic and walls of a structure can provide control of common pests in addition to known insulation benefits such a robust thermal envelope and acoustic noise-canceling properties. The EPA regulates this type of general-use pesticide within the United States allowing it to only be sold and installed by licensed pest management professionals as part of an integrated pest management program.[50] Simply adding Boron or an EPA-registered pesticide to an insulation does not qualify it as a pesticide. The dosage and method must be carefully controlled and monitored.

Rodent control is vital in cities.[51]: 133  New York City and cities across the state dramatically reduced their rodent populations in the early 1970s.[51]: 133  Rio de Janeiro claims a reduction of 80% over only 2 years shortly thereafter.[51]: 133  To better target efforts, London began scientifically surveying populations in 1972 and this was so useful that all Local Authorities in England and Wales soon followed.[51]: 133

Several wildlife rehabilitation organizations encourage natural form of rodent control through exclusion and predator support and preventing secondary poisoning altogether.[52] The United States Environmental Protection Agency notes in its Proposed Risk Mitigation Decision for Nine Rodenticides that "without habitat modification to make areas less attractive to commensal rodents, even eradication will not prevent new populations from recolonizing the habitat."[53] The United States Environmental Protection Agency has prescribed guidelines for natural rodent control[54] and for safe trapping in residential areas with subsequent release to the wild.[55] People sometimes attempt to limit rodent damage using repellents. Balsam fir oil from the tree Abies balsamea is an EPA approved non-toxic rodent repellent.[56] Acacia polyacantha subsp. campylacantha root emits chemical compounds that repel animals including rats.[57][58]

Insect pests including the Mediterranean flour moth, the Indian mealmoth, the cigarette beetle, the drugstore beetle, the confused flour beetle, the red flour beetle, the merchant grain beetle, the sawtoothed grain beetle, the wheat weevil, the maize weevil and the rice weevil infest stored dry foods such as flour, cereals and pasta.[59][60]

In the home, foodstuffs found to be infested are usually discarded, and storing such products in sealed containers should prevent the problem from reoccurring. The eggs of these insects are likely to go unnoticed, with the larvae being the destructive life stage, and the adult the most noticeable stage.[60] Since pesticides are not safe to use near food, alternative treatments such as freezing for four days at 0 °F (−18 °C) or baking for half an hour at 130 °F (54 °C) should kill any insects present.[61]

The larvae of clothes moths (mainly Tineola bisselliella and Tinea pellionella) feed on fabrics and carpets, particularly those that are stored or soiled. The adult females lay batches of eggs on natural fibres, including wool, silk, and fur, as well as cotton and linen in blends. The developing larvae spin protective webbing and chew into the fabric, creating holes and specks of excrement. Damage is often concentrated in concealed locations, under collars and near seams of clothing, in folds and crevices in upholstery and round the edges of carpets as well as under furniture.[62] Methods of control include using airtight containers for storage, periodic laundering of garments, trapping, freezing, heating and the use of chemicals; mothballs contain volatile insect repellents such as 1,4-Dichlorobenzene which deter adults, but to kill the larvae, permethrin, pyrethroids or other insecticides may need to be used.[62]

Carpet beetles are members of the family Dermestidae, and while the adult beetles feed on nectar and pollen, the larvae are destructive pests in homes, warehouses, and museums. They feed on animal products including wool, silk, leather, fur, the bristles of hair brushes, pet hair, feathers, and museum specimens. They tend to infest hidden locations and may feed on larger areas of fabrics than do clothes moths, leaving behind specks of excrement and brown, hollow, bristly-looking cast skins.[63] Management of infestations is difficult and is based on exclusion and sanitation where possible, resorting to pesticides when necessary. The beetles can fly in from outdoors and the larvae can survive on lint fragments, dust, and inside the bags of vacuum cleaners. In warehouses and museums, sticky traps baited with suitable pheromones can be used to identify problems, and heating, freezing, spraying the surface with insecticide, and fumigation will kill the insects when suitably applied. Susceptible items can be protected from attack by keeping them in clean airtight containers.[63]

Books are sometimes attacked by cockroaches, silverfish, book mites, booklice,[64] and various beetles which feed on the covers, paper, bindings and glue. They leave behind physical damage in the form of tiny holes as well as staining from their faeces. Book pests include the larder beetle, and the larvae of the black carpet beetle and the drugstore beetle which attack leather-bound books, while the common clothes moth and the brown house moth attack cloth bindings. These attacks are largely a problem with historic books, because modern bookbinding materials are less susceptible to this type of damage.[65]

Evidence of attack may be found in the form of tiny piles of book-dust and specks of frass. Damage may be concentrated in the spine, the projecting edges of pages and the cover. Prevention of attack relies on keeping books in cool, clean, dry positions with low humidity, and occasional inspections should be made. Treatment can be by freezing for lengthy periods, but some insect eggs are very resistant and can survive for long periods at low temperatures. Approximately 1.5% to 3.8% of books are infested by pests each year, affecting millions of books globally.[66]

Various beetles in the Bostrichoidea superfamily attack the dry, seasoned wood used as structural timber in houses and to make furniture. In most cases, it is the larvae that do the damage; these are invisible from the outside of the timber but are chewing away at the wood in the interior of the item. Examples of these are the powderpost beetles, which attack the sapwood of hardwoods, and the furniture beetles, which attacks softwoods, including plywood. The damage has already been done by the time the adult beetles bore their way out, leaving neat round holes behind them. The first that a householder knows about the beetle damage is often when a chair leg breaks off or a piece of structural timber caves in. Prevention is possible through chemical treatment of the timber prior to its use in construction or in furniture manufacturing.[67]

Termites with colonies in close proximity to houses can extend their galleries underground and make mud tubes to enter homes. The insects keep out of sight and chew their way through structural and decorative timbers, leaving the surface layers intact, as well as through cardboard, plastic and insulation materials. Their presence may become apparent when winged insects appear and swarm in the home in spring. Regular inspection of structures by a trained professional may help detect termite activity before the damage becomes substantial.;[68] Inspection and monitoring of termites is important because termite alates (winged reproductives) may not always swarm inside a structure. Control and extermination is a professional job involving trying to exclude the insects from the building and trying to kill those already present. Soil-applied liquid termiticides provide a chemical barrier that prevents termites from entering buildings, and lethal baits can be used; these are eaten by foraging insects, and carried back to the nest and shared with other members of the colony, which goes into slow decline.[69]

Mosquitoes are midge-like flies in the family Culicidae. Females of most species feed on blood and some act as vectors for malaria and other diseases. Historically they have been controlled by use of DDT and other chemical means, but since the adverse environmental effects of these insecticides have been realized, other means of control have been attempted. The insects rely on water in which to breed and the first line of control is to reduce possible breeding locations by draining marshes and reducing accumulations of standing water. Other approaches include biological control of larvae by the use of fish or other predators, genetic control, the introduction of pathogens, growth-regulating hormones, the release of pheromones and mosquito trapping.[70]

Birds are a significant hazard to aircraft, but it is difficult to keep them away from airfields. Several methods have been explored. Stunning birds by feeding them a bait containing stupefying substances has been tried,[71] and it may be possible to reduce their numbers on airfields by reducing the number of earthworms and other invertebrates by soil treatment.[71] Leaving the grass long on airfields rather than mowing it is also a deterrent to birds.[72] Sonic nets are being trialled; these produce sounds that birds find distracting and seem effective at keeping birds away from affected areas.[73]

cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ISBN 9781845938178.

Seattle (see-AT-əə l) is the most heavily populated city in the U. S. state of Washington and in the Pacific Northwest region of The United States and Canada. With a population of 755,078 in 2023, it is the 18th-most heavily populated city in the USA. The city is the county seat of King County, one of the most populous area in Washington. The Seattle metropolitan area's populace is 4. 02 million, making it the 15th-most populous in the USA. Its development rate of 21. 1% between 2010 and 2020 made it one of the country's fastest-growing big cities. Seattle is positioned on an isthmus in between Puget Noise, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and Lake Washington. It is the northernmost significant city in the United States, situated about 100 miles (160 km) south of the Canadian boundary. A gateway for trade with East Asia, the Port of Seattle is the fourth-largest port in North America in regards to container handling since 2021. The Seattle area has been occupied by Native Americans (such as the Duwamish, who had at least 17 villages around Elliot Bay) for at the very least 4,000 years prior to the very first permanent European settlers. Arthur A. Denny and his group of vacationers, consequently known as the Denny Celebration, showed up from Illinois using Rose City, Oregon, on the schooner Specific at Alki Point on November 13, 1851. The settlement was relocated to the eastern shore of Elliott Bay in 1852 and called "Seattle" in honor of Chief Seattle, a prominent 19th-century leader of the local Duwamish and Suquamish people. Seattle presently has high populaces of Native Americans along with Americans with strong Asian, African, European, and Scandinavian origins, and, since 2015, hosts the fifth-largest LGBT community in the U. S. Logging was Seattle's initial significant sector, but by the late 19th century the city had become a business and shipbuilding facility as a portal to Alaska throughout the Klondike Gold Rush. The city grew after The second world war, partially due to the neighborhood business Boeing, which established Seattle as a center for its production of airplane. Beginning in the 1980s, the Seattle location turned into a technology center; Microsoft established its head office in the area. Alaska Airlines is based in SeaTac, Washington, serving Seattle–-- Tacoma International Airport, Seattle's global airport terminal. The stream of new software, biotechnology, and Web companies resulted in an economic resurgence, which enhanced the city's populace by nearly 50,000 in the decade in between 1990 and 2000. The culture of Seattle is heavily specified by its substantial music history. Between 1918 and 1951, virtually 24 jazz bars existed along Jackson Street, from the present Chinatown/International Area to the Central District. The jazz scene supported the early occupations of Ernestine Anderson, Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, and others. In the late 20th and very early 21st century, the city additionally was the origin of numerous rock musicians, consisting of Foo Fighters, Heart, and Jimi Hendrix, and the subgenre of grunge and its introducing bands, including Alice in Chains, Paradise, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and others.

.I’ve been a client of Parker Eco Pest Control for two years & I’ve been so pleased with their service. Their call center/customer service is so easy to communicate with and they are so helpful if I need to adjust my schedule. The employees who come to my house are always so professional. They do a great job and I highly recommend this family-owned business.

Ask for Kevin if you can choose your tech - He's very helpful and its evident that he truly cares that you are happy with their services. He has visited our home numerous times and is always professional, friendly and best of all - they produce results. My favorite outcome was when we had hundreds of spider webs surrounding our home and they would reemerge when we "irradicate" them ourselves. With one simple treatment Kevin got rid of the Spiders overnight for the entire season. Same with the mice!

Helped us get rid of rodents in a matter of weeks! Chris is so knowledgeable and friendly. Outstanding service. We are on a quarterly service plan with them and it’s one of the best investment we have made for our house!

I've been very happy with Parker. I started with just a one-off treatment, but they were great to work with, so I went to the quarterly plan. We have persistent ant problems, so it does need regular treatment to keep it in check. The folks from Parker are always super responsive and willing to come out for repeat free visits as much as needed if we see any bloom of ant activity in the time between quarterly visits.

I hired Parker Eco to deal with my rodent issues. At first the work that was done wasn't quite up to my satisfaction however Chris, after hearing my experience, took the responsibility to throughly assess the situation and to address the rodent activities. This is how businesses should be run. Fair, competent with good customer service. It's no coincidence that they have a high rating and I wouldn't hesitate to recommend to anyone I know. Thank you Chris. I will be calling you again for my future services!!!